How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, and appropriate levels of hate

On Harry Browne's "The Frontman", and finding the worst in things (for a good reason)

1

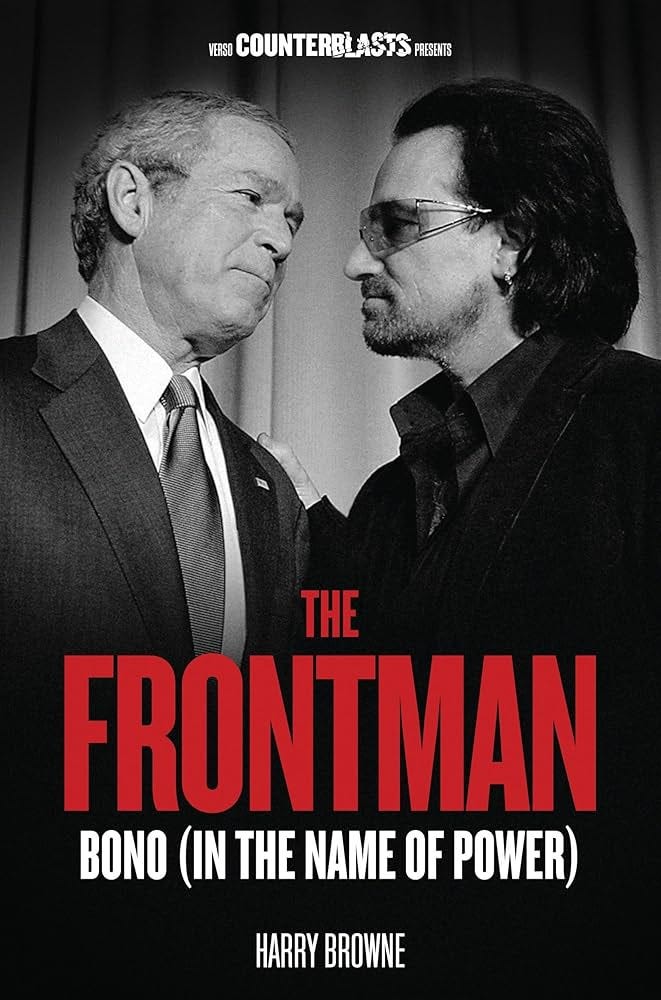

This isn't supposed to be book club, but for the second time this year already, a book has shaped my thoughts on this month’s topic of choice. The book in question, this time around: Harry Browne's The Frontman, which I picked up from my library out of an act of penance for my continued fascination in this god-forsaken band. There’s always been a bad energy hovering around U2’s positioning as multi-millionaires, and obvious from even your first impression of the book’s cover The Frontman seeks to condense that energy into one self-described “counter-blast”, investigating Bono’s position in philanthropic causes adjacent to some of the worst people this side of the Reagan administration. It’s an intelligent and conscientious insight into the Bono’s politics (& to an extent, all of his compatriots in and out of U2), as well as how he ended up drifting right on the compass despite all indications towards the opposite.

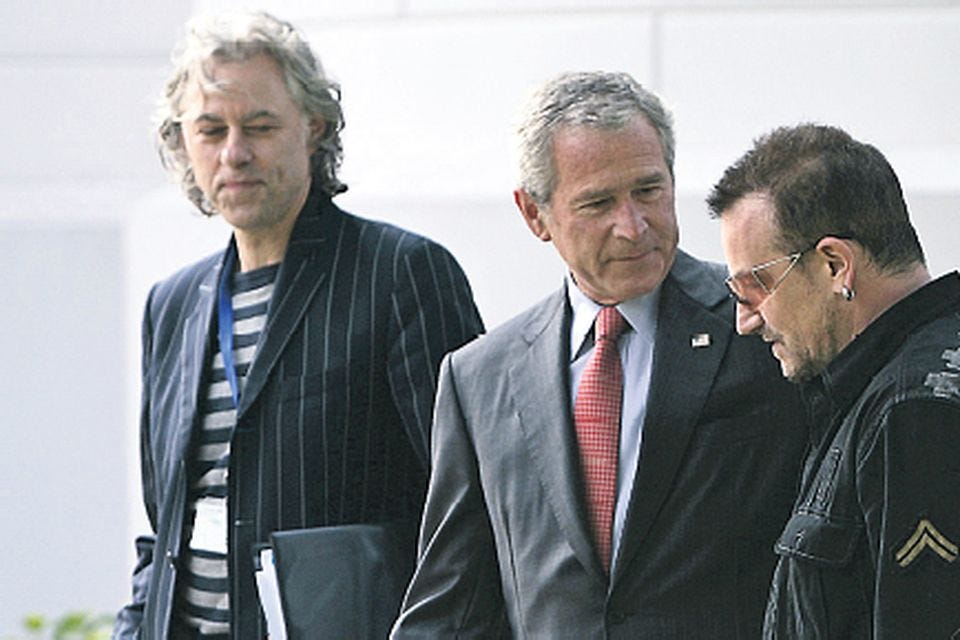

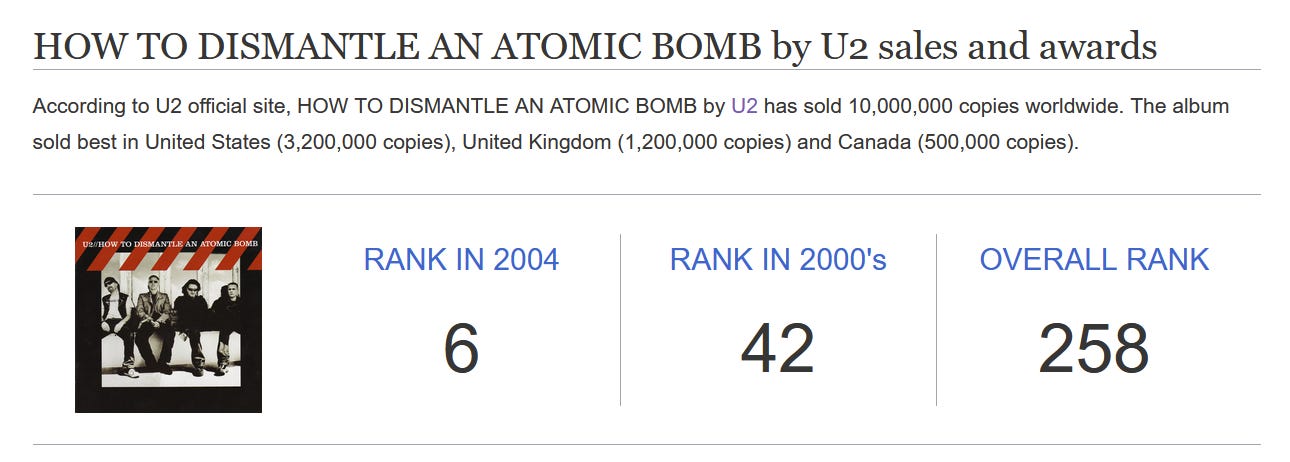

While the book spans nearly the band’s entire career, things seem to come to a head in 2005, the same year the excessively profitable Vertigo tour supporting How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb hit the road. There’s plenty of reason to narrow in on 2005 as the year Bono's public image fully began its descent into hell. Not least because of the tepid response to following up their "back to basics rawk" album with... another one, but also because of Bono's associations with the deeply polarizing Dubya administration, all the tax avoidance scandals, and their endless series of capitalist projects. There's also the self-congratulatory efforts of the (RED) brand, the celebrity sludge of the Live 8 concert, and the sensationalism of the 2005 G8 summit, to skim over a few of the topics The Frontman dives into thoroughly.

This certainly isn't the first time I've written about the crossroads of an album and the real-world conditions that allowed for its creation, and I'm sure it won't be the last. I don’t need to belabor just how much the stories we collectively tell ourself around a piece of work inform the work, whether it's the artist's lives or their significant life events or whatever. However, it’s worthwile to note it’s usually exclusively to the benefit of the work: we gain understanding, we gain empathy, we feel closer to the artists behind its creation. And in some instances, there too might be details and subtle flourishes that you would’ve never noticed had it not been for the artist pointing it out in interviews or discussions or whatever additional material. It's symbiotic: the work benefits from your deeper understanding, at the same time as you gain from whatever the work offers to you.

But How to Dismantle seems to spin that construct on its head. The stories that inform the record’s creation, unlike much that’s come before it, actively and consistently undermine its content; put another way, that relationship between the work and its conditions has become parasitic. In the dark, a song like "Love and Peace or Else" is a paint-by-numbers alt-rock tune with vapid lyrics, ultimately benign, but when paired with the backdrop of Bono cozying up to world oligarchs and billionaires (including Sachs of Goldman-Sachs of all people!) in service of the neoliberal facade of peace, a song about hunting for world peace feels torturously ironic. The tagline of "Crumbs From Your Table" is verbatim from Bono's own outcries to world leaders for debt cancellation in Africa, an effort which claimed itself as wildly bipartisan and successful while not actually providing any support and arguably worsening the situation in Africa. And let's not forget worldwide laughing-stock "Vertigo", whose radio-ready chorus was the perfect soundtrack to advertising the new Apple iPods, rallying behind the same music industry major-label structure that chewed up careers and spat them out for profits. These were songs that were already pretty empty, and yet somehow learning about them more hollows them out even further, shrinking my empathy.

When I initially gave How to Dismantle a second try, plugged into my earbuds while mindlessly folding gift bags for a family event in India, I noted that it was great if I completely turned my brain off. Some of these songs really do sound great: I adore the return of Edge's dotted-note delay-pedal riff on City of Blinding Lights, and honestly after 9 months of Pavloving myself I can kinda dig the hard rawk of Vertigo.1 But the catch is that they actively crumble under deeper thought; any further analysis - as simple as reading the lyrics, or my standard procedure of perusing on Wikipedia - would easily pierce any delusions that there might be something with serious depth under those guitars and those track titles. It's a worse fate than that of boilerplate indie pop, which at least has the grace to remain neutral towards the outside world, knowing better than to embarrass yourself.

It's almost cruel to contrast the politik of the Bono of 1984 to the Bono of 2004 (let alone to the Bono of 2024...). I reckon the version of him in his 20s would reel at the idea of being such a blatant sell-out, to even entertain the idea that the solution to his world-weariness is to seek guidance from the people who uphold the status quo, those guys in suits who maintain the structures of inequality he sought to fight. And even if he was secretly harboring all of those sentiments from the very start, the case study hits me hard at the very least - I loathe the idea of growing significantly more conservative as I grow older, a sickness that seems to befall anybody that relaxes their ability to stay active, stay connected, remain in-touch with the version of themself that cared about the injustice of the outside world. I suppose that's why I write.

2

One of my most consistent daydreams is someday being just famous enough via music - ideally, big enough to pack midsize venues, not big enough to get creepy parasocial emails - to participate in my own "What's In My Bag?" episode, whether solo or as a part of whatever group I happen to be a member of at the time. It's probably the greatest series on the web featuring artists talking about music in a way that's totally unburdened with the constructs of online music. Doesn't matter if they love, hate, or barely know the records they're showing to the camera, they’re wells of endless insight and memorable tales.2 God knows how many of these I’ve watched featuring artists I don’t know - sometimes that’s exactly what gets you onboarded.

A facet of this daydream at the moment is co-mingled with my obtuse interest in How To Dismantle. In 10 years' time I'd love to be standing in Amoeba's L.A. branch, flip up a $5 beaten-up vinyl copy of it, and say to the camera "this is my favorite bad album of all time", specifically despite being such an obvious tagline I don't think it's ever been uttered a single time on the show. People mostly buy stuff because they like it, other times they're just curious, and very rarely they'll say they don't get it and would like to… but never has anyone been so confident that they think an album is bad and are still buying it anyways, if only to gawk at the car crash. Give me a platform and I'll be that guy.

I've always felt there's been a unspoken conflation between being invested in something and liking said thing. Not to be conflated with "so bad it's good": indie theaters have been re-running The Room since it was reclaimed as one of the best unintentional comedies of all time, and there's been plenty of hysteria in music-centric circles online around Corey Feldman's bizarro Angelic 2 The Core. But those have always been one-off gaffs, never to be examined further or more critically; surely if you keep returning to something it's because you see something in it? Sane people generally avoid wasting time on whatever doesn't bring them joy, or worse, wasting time on intentional, active hate.

And to at least face the current state of the world, it’s easy to feel like the last thing we need is hate. Bland, empty optimism, I know. But like much of my re-evaluations over the last few years, you recognize the wisest people you hear from know how to temper that edge, where it’s appropriate to be negative and be critical and where it isn’t. Good analysis always seems to be sharpening the blade, not to fall on either side of it into blind hatred or toxic positivity.

I'd argue that, even past any regular revisitations of that which you might've initially put off, what you don't like is as worthwhile to explore as what you do like. Put as an idiom that a white mom might put up on her Facebook profile, the absence of love somewhere makes the presence of love elsewhere even stronger. Figuring out which elements fail might greatly enhance whatever elements you've continued to enjoy and appreciate. Maybe you come to recognize that some specific element to a favorite record was never the linchpin to your appreciation; I loathe the mid-fi alternative rock sound in plenty of places on How to Dismantle, but have always loved it on New Adventures in Hi-Fi. Or maybe you come to pay closer attention to the circumstances of the fuller picture before a verdict, How to Dismantle being the product of middle-aged men opting into a commercial sound, shooting for ultimate populism even if we ignore Bono's buddy-buddying in the Oval Office with Dubya. Or maybe its failures highlight the traps that your favorites avoid; Bono's lyrics are dry as hell, the chord shifts and verse-chorus-verse structures can sometimes be so painfully predictable, you can only do so many soaring choruses before it feels like music for the masses.

Even if I harbor a negative opinion on How to Dismantle, for obvious reasons, that doesn't stop me from being interested in it even if primarily for its failures. Honestly, I think everyone should have a favorite bad album - something that fails and fails agains but wouldn’t be anything if not for those failures. Taste is less like a series of disparate, random affects and more like a singular, intensely intricate, black box function, one that takes in a bunch of junk ideas and outputs dopamine, and I'd like to think our mission is to reverse engineer that function to the best of our ability, even if that means being a little mean once in a while.

It helps I was not around to hear Vertigo ad infinitum on MTV in 2004.

If you've never watched an episode of it, you might be living under a rock. Personal recs are for Julian Lage, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, & Kathleen Hanna.